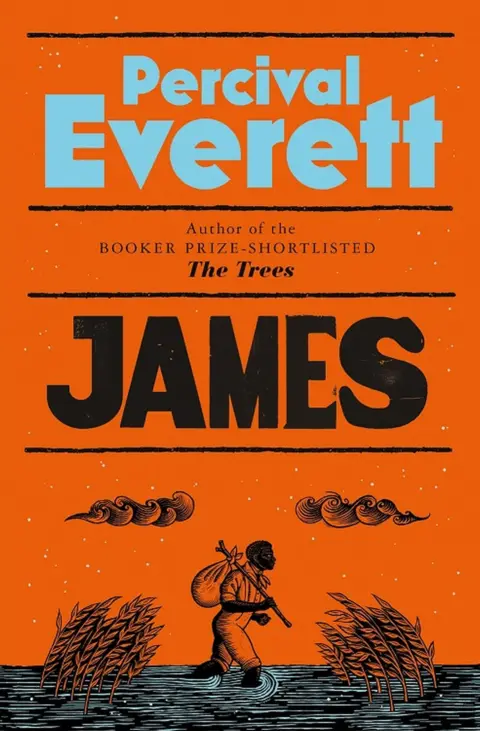

Percival Everett: Why I Rewrote Huckleberry Finn to Give Slave Jim a Voice

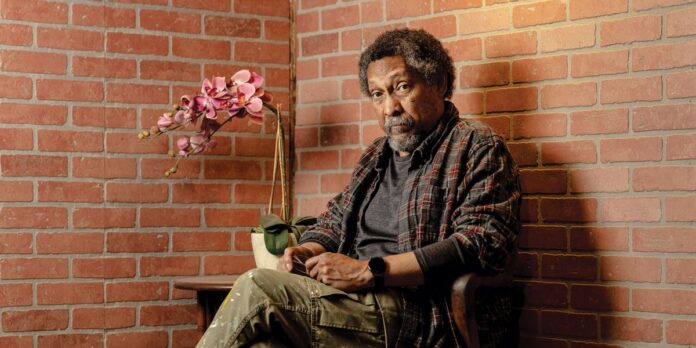

Percival Everett, the acclaimed author of the novel “Erasure” which was adapted into the Oscar-winning film “American Fiction,” found inspiration for his latest book, “James,” while playing tennis. After hitting a ball “wildly” out of court, he wondered if anyone had ever written “Huck Finn” from Jim’s perspective. When he discovered that no one had, Everett took it upon himself to give the runaway slave Jim a voice.

Everett’s resulting novel has been hailed as a “masterpiece” by critics, with many praising his skill as “an American master at the peak of his powers.” In Mark Twain’s original “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn,” Jim is a secondary character, written from the perspective of Huck, a boy who fakes his own death to escape his abusive father. Jim, on the other hand, is a runaway slave who is about to be sold to a new owner. As Everett points out, Jim “doesn’t get to speak” in the original novel, and he sought to change that by giving him agency and a voice of his own.

Redefining Jim

In an interview ahead of the novel’s publication in the UK, Everett reflects on the current state of racial unity in the US, expressing his belief that the country has taken steps back in recent years. He highlights the “alarming rate” of police killings of people of color, describing them as modern-day lynchings, and emphasizes that the legacy of slavery has still not been fully addressed.

By reimagining Jim as James, a character who writes himself into existence with a stolen pencil stub, Everett humanizes him and moves away from the stereotype created by Twain. In “James,” Jim is a literate and literary character who shares his thoughts on the world, his nation, and racism. He engages in conversations with philosophers in his dreams and possesses wisdom beyond his circumstances.

Everett employs a powerful device to change the perspective in his novel. When the slaves are in the presence of white people, they speak in a dumbed-down dialect, deliberately making themselves sound ridiculous and gullible. However, when they are not being overheard, they use an eloquent and highly intellectual form of English, discussing topics such as “proleptic irony.” This hidden language serves as a means of communication among the enslaved, imprisoned, or oppressed, allowing them to speak freely without their oppressors understanding.

In the book, James explains to his daughter and the other children he is schooling that they are expected to sound a certain way to meet the expectations of white people. He comments on the impact of feeling inferior due to these expectations, stating that “the only ones who suffer when they are made to feel inferior is us.” Everett’s use of irony is evident throughout the novel, as he challenges societal norms and expectations.

The Power of Language

Language plays a significant role in Everett’s novel, just as it does in Twain’s original. While Twain’s work is anti-slavery, its use of the n-word over 200 times has made it controversial and challenging to teach in modern educational settings. “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” is no longer included in the GCSE or A-Level syllabus, and some schools in America have even banned the book.

Everett, however, is opposed to book banning and sees it as a form of control. He acknowledges that Twain’s novel is a “wonderful” and “remarkable achievement” in American literature, as it explores the complexities of race through the eyes of an adolescent grappling with his friendship with Jim, who is both a person and property. While Everett also uses the offensive term in his novel, he does so less frequently than Twain, and his intention is to provoke thought and challenge readers rather than perpetuate racism.

As a prolific author with 24 novels to his name, many of which delve into the topic of race in America, Everett continues to push boundaries and spark conversations through his writing. By giving Jim a voice in his reimagining of “Huckleberry Finn,” he invites readers to reconsider the perspectives and experiences of marginalized characters, ultimately contributing to a more inclusive and nuanced understanding of American literature and history.